Modernas No More: A Rare Success from the End of an Era for Biotech

Complexity is making it unlikely for new Moderna-like integrated biotech companies to emerge; instead, partnerships between specialists will keep fueling drug development.

If you enjoy these posts, please add a comment or like above, and share it with one other person who may also like it!

Depending on whether you got the Pfizer or Moderna Covid-19 vaccine, you were either the beneficiary of an old and diminishing model of drug development, or of a surging alternative to the way companies discover, test, and sell drugs - and it’s probably not the one you think.

Two Opposing Models

Pharma companies have traditionally been vertically integrated, discovering, testing, and selling most of their drugs themselves. Even biotech innovators like Vertex, Amgen, Regeneron, and Genentech embodied that approach. Since the dawn of the biotech industry in the 1970s and 80s, these companies, equipped with new techniques to engineer biology, competed directly with existing pharmaceutical giants. Yet they too continued to operate mostly in silos, managing everything from research to marketing entirely on their own.

Today, that is an increasingly challenging feat especially given the complexity of many new drugs. In fact, compared to older-than-a-century drugs like aspirin which are more like grenades, modern drugs are designed to be precision-engineered drones that hone-in to solve one specific problem.

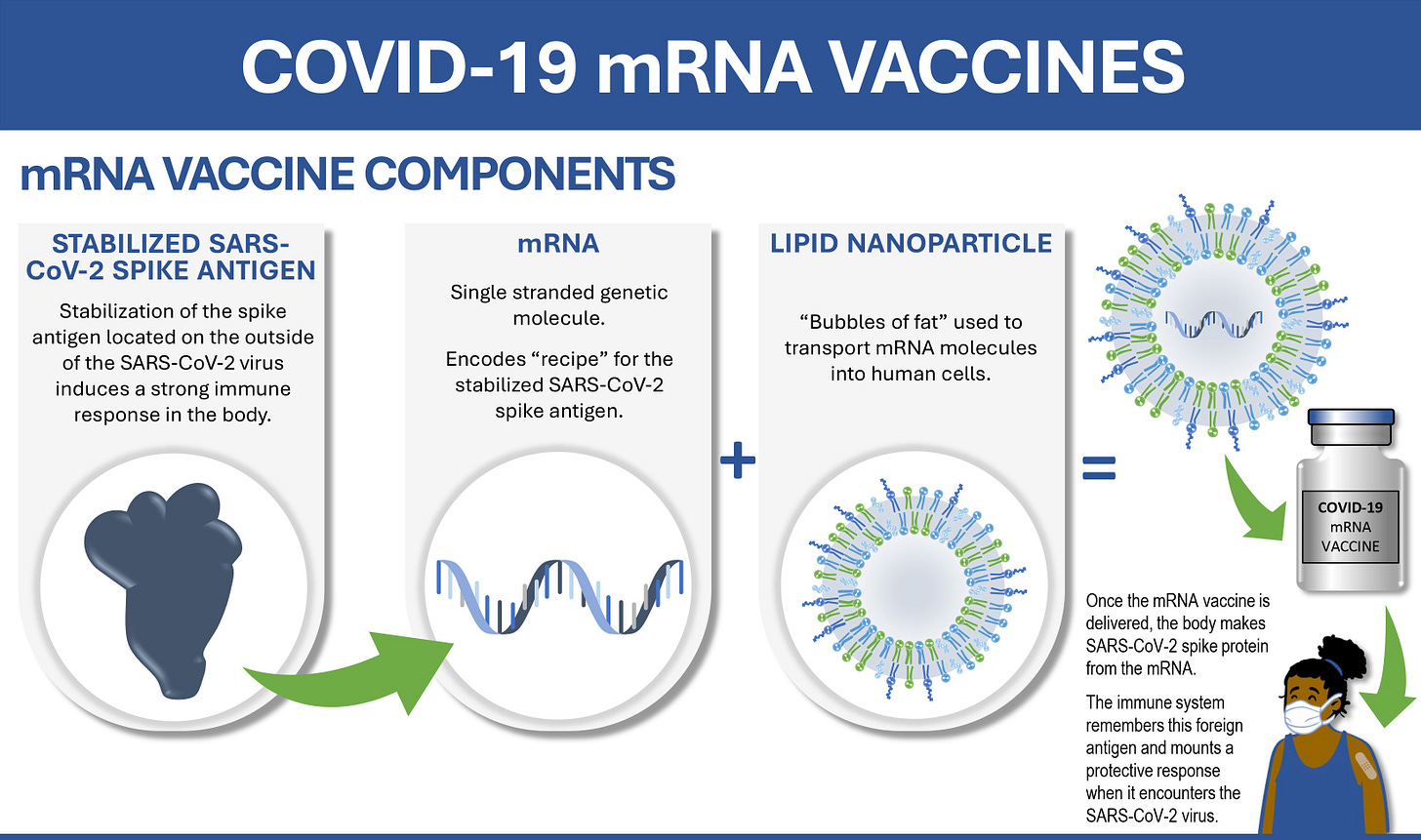

The Covid-19 vaccine, for instance, isn’t just one product but two very complex biological products in one — a messenger RNA sequence encoding the recipe for a viral protein enveloped in a nanoparticle that can deliver it into the body. And designing it is technically very challenging. The delicate RNA can get shredded by other proteins in our cells. Or the nanoparticles could be ineffective at activating our immune systems unless some specific lipid molecules are used. The final formulations of the successful mRNA vaccines were a result of decades of research at labs in Moderna and across the world.

Moderna, founded decades after the first wave of biotech trailbrazers, was a rare new company that could still follow the traditional model. Since its inception in 2010, Moderna prioritized developing mRNA-based treatments for cancer and other severe diseases which were much more lucrative than vaccines. All of that research and expertise were waiting in the wings when a once-in-a-century need for rapid vaccine development emerged. Hence, Moderna was fortuitously poised to design, test, and sell a Covid-19 vaccine without help from any of its peers.

On the other hand, Pfizer’s mRNA vaccine represents the way such complex drugs are more commonly developed today: the result of technology and expertise from three different teams coming together. BioNTech, a European company that specializes in RNA engineering technology provided the expertise needed to encode the Covid-19 spike protein. Acuitas, a Canadian company, had been separately developing its expertise in using the most potent and safest lipid nanoparticles for delivering drugs to human cells. And finally Pfizer, a 170-year-old pharma company, put the pieces together. It deployed its formidable mass production and clinical development capabilities to leapfrog Moderna and produce the first Covid-19 vaccine to gain regulatory approval.

Harder Drugs and Tougher Markets

The recent success of the collaborative model Pfizer used is driven by increasing complexity across every aspect of drug development.

Biotech companies routinely spend tens of millions of dollars on laboratory and animal studies before being allowed to start human trials. Even then, only 10% of those candidates make it past the multiple phases of clinical trials. Those trials are intended to ensure that these complex drugs are not causing any long-term side effects and are indeed more effective than any existing options for patients. The rare, successful few that do get approved only raise the bar higher for other new drugs down the line. To show an improvement, future trials need to be conducted with even more participants. The average new drug now costs $2B in research and development, more than 6-fold the estimate from the 1980s.

Once approved, these drugs then face stiff competition for sales. While smaller companies in the late twentieth century could see themselves competing with established players, facing off against the sales and marketing teams of big pharma is much more onerous for biotech companies today.

Finding Partners to Innovate and Sell

Faced with this reality, the industry has evolved a “division of labor” approach.

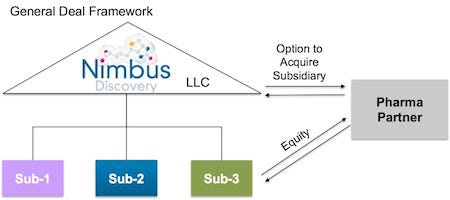

Most biotech companies today specialize in one specific scientific problem within drug development. When they solve that problem in small-scale studies, they hand their solutions off to large pharma companies like Pfizer to do the rest. Large companies benefit from this model too. Althought they are commercial powerhouses, their research teams often struggle to match the innovation of niche biotechs. A 2023 report in Nature Reviews Drug Discovery found that, “the business model of the top 20 biopharma companies in recent years has largely been built on external innovation.”

Such an external innovation model itself, however, is not fundamentally new. The first drug developed by Genentech, one of the pioneering biotechnology companies, was human insulin. At the time, patients with diabetes received insulin harvested from cows and pigs. In 1978, Genentech scientists showed that they could instead produce insulin from bacteria. But as a small company, they couldn’t scale up manufacturing and conduct clinical trials. So, Genentech partnered with Lilly, which rapidly tested the drug and secured FDA approval by 1982, less than 4 years from the initial proof of concept.

Genentech, though, didn’t stop there. Capitalizing on their success with insulin, Genentech developed another hormone therapy. In just 3 more years, the company tested, secured approval, and marketed the new drug completely by itself, charting a course to become an enduring drug development company itself.

Today, a typical drug takes 10-12 years to get to FDA approval.

Hence, most biotech companies never take the second step which led Genentech to sustained growth. As a result of increased complexity in drug development and tightening market forces, they must continue relying on the collaborative method or get acquired. Roughly 70% of drugs are now developed using this partnering model.

The Money Follows

Investors in biotech companies see this division-of-labor as an opportunity to fund two new categories of specialized companies.

At the initial design stage, a new generation of “platform companies” are specializing in using automation, protein design, artificial intelligence, or other proprietary skills to generate an incredibly sophisticated range of possible blueprints. Their clients, other drug companies, hope that such designs are more likely to succeed through development milestones. A McKinsey report summarizing early-stage biotech investing in 2023 stated that platform companies “have dominated biotech funding over the past few years because they typically promise to address a broad array of [applications] over time.”

At the next stage, which involves lab, animal, and human trials, many biotech companies today are effectively “single-asset companies.” That means their teams take all potential designs that could solve one hard therapeutic problem, and tweak them until they identify the single most promising drug candidate. If they succeed, these companies hope to get acquired by a large pharma company, which would test the asset in larger, more expensive clinical studies.

In an interview in 2021, veteran biotech investor Francesco De Rubertis, whose career has been built on investments in traditional biotech companies, said he would now “solely invest in startups that only commit to develop one molecule… If you can create a single asset company around a single asset with top people that commit their professional career to [it, that] represents a high conviction asset.”

In many cases the platform companies themselves are launching single-asset companies, to develop their initial designs into drug candidates that are ready for pharma to plug into their engines.

The End of an Era for Biotech?

A vanishingly small number of companies founded in the last 20 years have access to the path that led Genentech and Moderna to the growth they achieved. Moderna, whose Covid-19 vaccine story is a lucky exception to this general trend, is also now facing challenges sustaining a pipeline of valuable new drugs.

Frequently, even companies that do develop a portfolio of products, ultimately get acquired by veteran pharma companies. That includes Genentech itself, which in 2009 was acquired by Roche, a pharmaceutical company founded in 1896.

As the era of vertically integrated biotech companies sunsets, drug development in the future will likely be distributed across specialized platform companies, transient early-stage biotech companies, and a smaller number of big pharmas with the marketing muscle.

This elevates the importance of productive partnerships as tools for innovations. And as I have previously written, if companies are willing to forge win-win partnerships through creative dialogue, that is bound to yield compounded results for both the industry and the patients it is meant to serve.

I’d love to hear your thoughts the comments below.

What's your favorite example of a company (biotech or otherwise) that had the potential to become an enduring player but was cut short by market forces?

What are some counterexamples - companies that have managed to climb uphill through complexity and compete with established players?

What are some of your favorite examples of win-win collaborations between big and small companies (biotech or otherwise)? What made them work so well?

Thank you to , , and for helping me edit this essay, my first as a part of ’s essay club!

Substack references:

: https://www.notboring.co/t/vertical-integrators

: https://centuryofbio.com

This was a lovely read! I love how the essay turned up (especially the wonderful pun in the title!)