If you enjoy these posts, please add a comment or like above, and share it with others!

On a pleasant April day in 2014, a few hundred people gathered at a landfill in Alamogordo, in the New Mexico desert, and awaited word from the hard-hatted crew who had spent the last few hours excavating decades of trash. When a Donny and Marie Osmond poster from the 1980s was found, they knew they were getting close. By early afternoon, the crowd was out of their folding chairs, toasting with cans and cheering. They had found it.

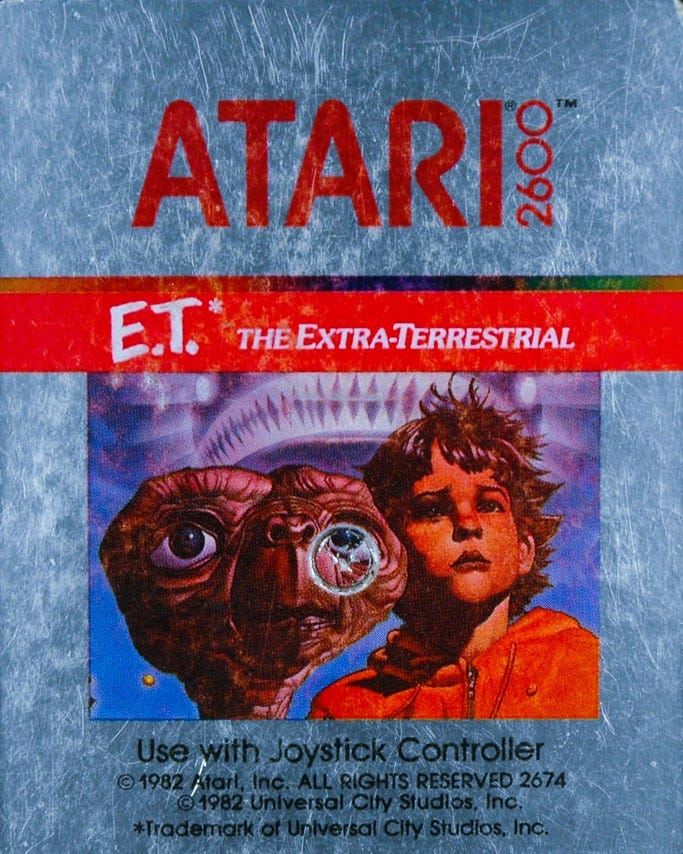

Hundreds of cartridges were excavated, while many more remained buried deeper, of Atari’s E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial, a video game that was so bad, it set off the biggest economic crash in the history of the gaming industry.

Among the onlookers was Howard Scott Warshaw, the man who had designed the fateful game 32 years earlier. He was surprised to find those cartridges buried there. Until then, he didn’t believe the Silicon Valley legend. But Atari, once the most successful video games company in the world, had indeed paid to dump truckloads of unsold and returned cartridges, even as their profits were plummeting in 1983. Those circumstances were emblematic of what led to Atari’s eventual demise.

E.T. was a terrible game. Although it started out with thrilling music and elaborate graphics, it went downhill quickly. Most players found it too difficult to control, disorienting, and confusing. At times, it wasn’t clear how certain parts were meant to be navigated. At other times, too many new characters showed up, chaotically. The lead character, E.T. itself, would repeatedly fall into pits that it sometimes couldn’t get out of, and when E.T. did make progress on its mission to return home, an FBI officer could randomly set it back.

Video games are incredibly hard to design because human emotional responses are complex and unpredictable. E.T. failed to strike one of the most important kinds of balance needed in any kind of game, between difficulty and reward. Games need to be hard enough to evoke some disquiet, but not so hard that they become disconcerting. In the case of E.T., it all came together very poorly.

When Warshaw, as a 23-year-old Computer Engineering master’s graduate, was hired by Atari in 1981, the company was at its zenith. It had dominated the gaming industry in the 1970s with very successful arcade games. Atari was now leading a revolution, bringing video games into middle-class homes with simple consoles that plugged into televisions and cartridges that summoned worlds to those screens. In 1980, the company made $2 billion.

The first game Warshaw developed was a best seller. Called Yar’s Revenge, it was designed to “grab someone right by their cognitive elements and not release them.” His next game, Raiders of the Lost Ark, based on the Steven Spielberg movie, did well too. So well, that in the summer of his second year working at Atari, Warshaw was in his second meeting with Spielberg, now discussing plans to make the Hollywood pioneer’s upcoming production into the next console favorite.

This time however, there was an unexpected challenge. Warshaw’s previous games, as was standard at the time, had been designed over five to seven months. Corporate negotiations for E.T. had delayed the start of development to late-July of 1982, just after the movie’s release. But it still had to be completed by September 1st, in order for copies to be available for the Christmas shopping season.

Warshaw had five weeks “and half of a day”, less than a fifth of the time it typically took.

Spielberg and Warshaw started with different visions for the game. Spielberg had imagined a simpler game, similar to PacMan. But Warshaw, whom Spielberg had called “a certifiable genius,” had no doubts he could pull off something more sophisticated. The objective would be for E.T. to collect pieces of a phone, so that he could dial home.

Warshaw recalls having no clue about the risk of building such a complex project over such a short period of time. With Spielberg persuaded, he got down to work, using every minute of those five-weeks-and-half-a-day that he could, to build the game.

He delivered the fully programmed game with unprecedented speed, and Atari, skipping any testing, went straight to production. The company manufactured five million cartridges of E.T. for a special Christmas launch. Warshaw was flown to London for its game’s premier. Incredibly, it seemed, he had done it. Hundreds of thousands of breathless kids were waiting for this moment, to “play the movie” that had been topping charts for nearly six months. And on Christmas morning, most of them were very disappointed.

Although the game saw healthy early sales because of the hype, soon everyone had heard about how frustrating it was. Sales stalled. Millions of cartridges went unsold, for months.

What went wrong for Atari with E.T.? How had such a prodigious developer working for the biggest video gaming company created a product so flawed?

Atari’s executives had put their developers in an untenable situation. To push for their misguided timelines, they moved a development system into Warshaw’s house so he wouldn’t lose time commuting. He even tried to time his sleep, thinking his brain would use the time to resolve problems he was stuck on. With all that, Warshaw was able to build a game in the compressed time that they had estimated.

But in hindsight, it is plain that their most disastrous error was to neglect testing the game. Play-testing is where groups of people representing various possible audiences for the game are invited to play it before it is available to everyone else. They also play another popular game and compare their experiences. Incorporating such trials early has become standard practice in many industries now.

When Atari was about to start manufacturing millions of E.T. cartridges, they should have been starting trials instead. According to Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman, game design experts and authors of Rules of Play (2003), Atari should’ve then taken the next five months to make the game better by trial-and-error. A survival-of-the-fittest design process is far superior to elaborately designing a complex game all upfront.

As sales of E.T. plummeted, they took everything down. In four years, the video game industry was selling a tenth of what they had been. Analysts believe that the gleaming new idea of in-home video games had started to dull; and poorly executed games like E.T. hastened the audience's disinterest. On Sept 26, 1983, Atari dumped, by some estimates, nearly a million unsold game cartridges in a pit in the desert. And suffered massive losses. What followed was a frantic series of more strategic missteps to deal with financial distress, leading to more failed launches. Atari was sold to a computer manufacturer in 1984.

Howard Scott Warshaw took a year off, worked as a real estate broker for some time, wrote a couple of unsuccessful books, made some documentaries about video games and Atari, and now practices as a therapist in the San Francisco Bay Area.

E.T. the game itself, became a legend, as the worst video game ever. That legend had drawn gamers, documentary filmmakers, and journalists from across the continent to New Mexico. They watched E.T. being resurrected from the mounds of trash. Warshaw witnessed what three decades earlier he couldn’t have foreseen would be the fate of the project on which he worked the hardest he ever did.

And to think it could have all turned out so differently. Atari and Warshan just needed a few more months to improve the game by selecting the fittest parts of the design and letting evolutionary design work its magic.

On this Substack, I will explore many more such examples from biotechnology, organizational design, pharmaceuticals, evolutionary biology, software, and others, in the quest to understand how design by trial-and-error works, where it fails, and when it thrives.

If you or someone you know may find that interesting, please subscribe, share, and feel free to get in touch!

Notes

99percentinvisble (Podcast) “The Worst Video Game Ever”; January 28, 2020

Interview with Howard Scott Warshaw: http://www.digitpress.com/library/interviews/interview_howard_scott_warshaw.html

Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals, Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman, MIT Press, 2003

fantastic read!

finding that Goldilocks zone is a lifelong struggle I find.. with direct reports at work, significant others..

This particular game was absolutely horribly frustrating btw. we had it in Atari 😅 I still remember the sound effect you got when you fell through invisible holes in the ground. there must be online browser based emulators out there..

this NPR story focusing on Warsaw reminded me of your post: https://www.npr.org/2017/05/31/530235165/total-failure-the-worlds-worst-video-game

turns out he became a therapist afterwards.. who knew.