Drugs in the Balance: FDA's Complex Job Safeguarding Health

RFK Jr. misunderstands the agency — Drug regulation is critical and complex (not corrupt)

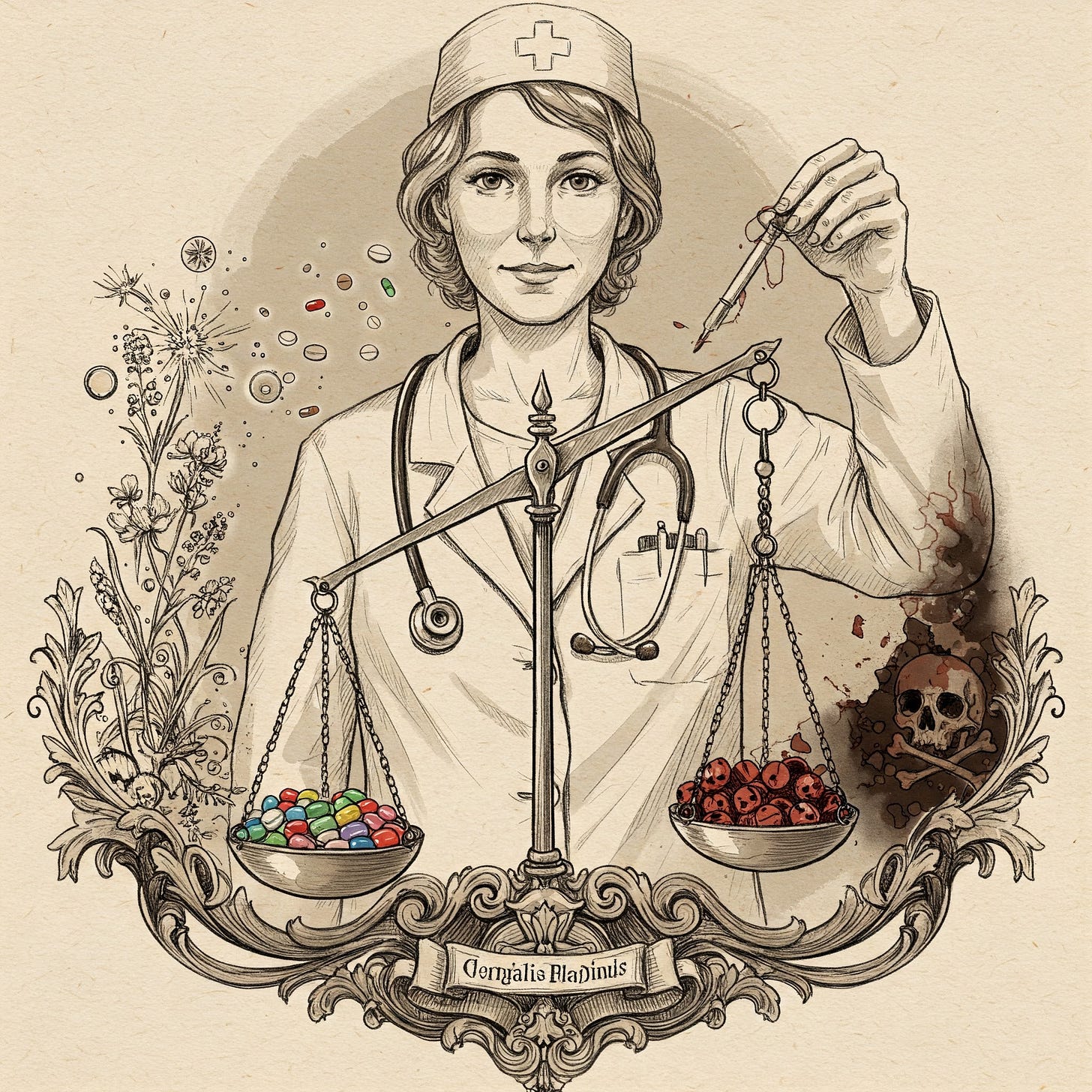

What side effects should we accept from a drug that fights a deadly cancer? Should the threshold be different for a psychoactive medicine meant to relax an anxious mind? Finding the balance between the risks and benefits of drugs — conventional or alternative — is tricky. But it is essential for public safety. RFK Jr.’s criticism of the FDA stems from what he considers an inconsistently stringent approval process. In fact, he misses the bigger picture.

In 1961, Professor Widukind Lenz, the head of Hamburg University’s children's clinic in West Germany, was visited by a distraught father with X-rays of his newborn daughter. She had extremely shrunken arms and legs from a devastating condition called phocomelia. Phocomelia is rare, found only once in every 150,000 births. Yet, six weeks before that man’s wife gave birth, his sister had also delivered a baby with this disease. Lenz was stunned. He left the room, returning with an image he had received just that morning of a third baby with identical deformities. With a sense of foreboding, Lenz manually scrutinized decades worth of hospital records. He discovered that in the 25 years leading up to 1955, just one such case was recorded from 212,000 births in Hamburg. But in just the prior twelve months, eight out of the 6,420 babies born in the city were phocomelic.

At nearly the same time on the other side of the world, William McBride, an Australian obstetrician, encountered the same terrible outbreak. Three babies were born with those very birth defects within five weeks. After days of studying the sparse body of knowledge around birth abnormalities, McBride developed an unimaginably unsettling hypothesis, the same conclusion that Lenz’s research would lead him to. A drug frequently taken by pregnant women was causing these horrific epidemics.

Beginning in 1957, Thalidomide had been promoted as a “safe wonder drug” to people of all ages across the world. Grünenthal, the drug’s original German manufacturer, marketed it as an alternative to contemporary sedatives that were addictive and bore significant risk of death from overdoses. They claimed thalidomide could help insomnia, depression, headaches, and morning sickness during pregnancy. In reality, many of the drug’s safety proclamations had never been tested beyond experiments in rats, and all its claims of beneficial effects had been discovered “by method of Russian Roulette” in uncontrolled observations in human patients. Because studies in rats had shown the drug to have no detrimental effects, Grünenthal convinced German regulatory authorities to allow use over-the-counter. This let the company circulate samples widely without monitoring any side effects.

Thalidomide was quite obviously far from a wonder drug. Over 40,000 people suffered irreversible nerve damage from its use. Even a single tablet, if taken early in pregnancy, caused disastrous effects on embryos. Between 8,000 and 12,000 babies were born with defects — more than half of whom did not reach adulthood.

Grünenthal had developed thalidomide by the standard practice of randomly modifying a known chemical (in this case, the amino acid glutamine) to create derivatives that might have useful properties. From there, initial tests are performed on animals, usually rats or mice. In the case of thalidomide, no amount of the drug showed any detrimental effects on either of these animals or their offspring. And they showed only a questionable mild sedative effect. The next critical step would usually involve testing on humans — but Grünenthal negligently declared that the question of safety had already been tackled in the animal studies. Only focusing on the drug’s potentially helpful effects in brief human trials and not any of its side effects was an enormous blunder, to say the least.

Sadly, it was a blunder accepted by most drug regulators across the world. But not by all.

Thalidomide was not marketed for morning sickness in the US, because Frances Kelsey, a medical officer at the FDA however was not convinced. A Ph.D. in pharmacology, Kelsey was thoughtful, rigorous, and unassuming. She was also unrelenting in her drive to protect people from the “real threat of pharmacological poisoning.” When considering the FDA application for thalidomide, she presciently wondered if the drug showed no perceptible effect in rats even at very high doses because it wasn’t getting absorbed by their digestive systems at all. Hence those experiments would be unilluminating about any impact on people. Despite provocative and intimidatory tactics by Grünenthal’s American partners, Kelsey delayed approving the drug, seeking more evidence of its safety. Those delays coincided with the early reports from West Germany including Lenz’s findings. By holding her ground, Kelsey halted thalidomide and saved hundreds of lives. President John F. Kennedy awarded her the President’s Award for Distinguished Federal Civilian Service in 1962.

Now decades later, JFK’s nephew, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the new Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has been very critical of the FDA. RFK Jr has voiced two main sets of concerns, that the FDA is:

too restrictive in regulating alternative treatments like psychedelics, herbal formulations, and nutraceutical supplements; and

too lenient in allowing pharmaceutical companies to promote their products despite known and potential side effects (including vaccines).

To him, all this means that the FDA is corrupt and that pharma companies have a heavy hand in influencing FDA policies1. There is obviously much more to it.

Working in the biotech industry for over a decade, I have witnessed the increasing complexity of drug development. As a part of teams that have received both favorable and extremely challenging feedback from the FDA, I have come to appreciate the remarkable role the agency plays in navigating the complexity of safeguarding public health

The FDA’s mandate is to evaluate whether a drug’s “expected benefits outweigh its potential risks to patients”, something that is far from as straightforward as it sounds. For example, Frances Kelsey, in interviews after the thalidomide tragedy admitted that she would have assessed the risk-benefit balance differently if thalidomide had been shown to have more helpful effects than sedation alone. And as we’ll see, decades later with more evidence available, the FDA did exactly that, to once again save more lives.

Although the FDA applies its inherently subjective yardstick as analytically as possible to conventional drugs, vaccines, and alternative medicines, the results are scarcely black-and-white. Such analyses primarily rely on randomized clinical trials. Drug applicants monitor a sufficiently large number of patients, half of whom take a candidate drug and the other half who are given a placebo. But both the benefits and detrimental side effects of many substances don’t reveal themselves right away. And most sellers of herbal extracts and psychedelic formulations rarely perform controlled studies. Hence their impacts on health remain inextricably conflated with other dietary or behavioral habits of people using such products.

Many natural ingredients have been adopted into conventional medicines. Aspirin (willow leaves for headache), quinine (cinchona bark for malaria), digitalis (foxglove plant for heart failure), and several other drugs are derived from traditional medicine practices. “There’s a name for alternative medicines that work,” said Joe Schwarcz, professor of chemistry and the director of the Office for Science and Society at McGill University in Montreal, in an interview. “It’s called medicine.”

But when they don’t work, the outcomes can be disastrous.

In 2004, the FDA banned supplements containing ephedra alkaloids, derived from a traditional Chinese medicine, because of its serious side effects, including deaths. Ephedra extracts were believed to help with colds, fevers, and even performance enhancement. However, a 2000 study in the New England Journal of Medicine found that its use led to severe disability and sudden cardiac death, especially in young adults. The ban was challenged by manufacturers but upheld by the US courts in 2006.

Several similar instances reveal the flaws with a common refrain that the safety and effectiveness of natural medicines are evident from their history of use over centuries. In fact, the story is much murkier. In cases like Ephdera, although the active ingredient is also toxic, it may still benefit a small category of patients in the right doses. However, those recommendations are impossible to make without controlled studies. In other cases, impurities and a mix of active ingredients in herbal extracts complicate matters.

Take Kava, an herb native to the Pacific islands known to help reduce anxiety and to have mild sedative effects. The FDA and NIH advise against its use because Kava has been linked to serious liver damage and instances of death, even when taken at normal doses. Some studies suggest that beverages made from Kava root may be safer than ones adulterated with the stem and leaves. In 2015, German courts found insufficient evidence to support a blanket ban on Kava. However, the FDA has maintained its position. In the absence of larger clinical studies with standardized formulations of the extract, its benefit-and-risk balance doesn’t meet justifiably high regulatory standards.

Similar issues have plagued most psychedelics, which despite the FDA’s flexibility, remain one of the most frequently cited pieces of evidence against the agency. The FDA has granted “breakthrough therapy” designation to psilocybin, MDMA, and LSD. However, the onus remains on potential manufacturers to develop satisfactory evidence of their benefits. The first such attempt by a company called Lykos Therapeutics, to seek marketing approval of MDMA for PTSD, was rejected by the FDA in 2024. Lykos was backed by the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, or MAPS, which has spun the rejection as the FDA’s attempt to safeguard the interests of pharma companies selling antidepressants. However, Lykos’ study was riddled with issues. Nearly a quarter of the trial participants dropped out, one faced sexual abuse, and insufficient information was collected about the frequency of life-threatening side effects like heart palpitations. Upon review, a panel of independent advisors to the FDA voted 10-1 against approval. Still, multiple other companies are studying psilocybin and LSD in larger clinical trials, which could form the basis for a potential approval of those drugs at the appropriate doses for the right set of patients.

Unfortunately, building evidence about whether the benefits of a substance outweigh its risks is an expensive endeavor, which can often only be undertaken by pharma companies with large research budgets. To RFK Jr, it looks like corruption when most FDA-approved medicines are from pharma companies. But he has it backward. It’s not that the FDA only approves drugs from mainstream pharma companies. Instead, mainstream companies only choose to develop those drugs that are approvable by the FDA.

And sometimes the drugs approved by the FDA do bear serious side effects, but there are good reasons for such flexibility too. Even with it comes to substances as controversial as thalidomide. Decades after the tragedies in the 1950s, scientists learned that it affected the growth of embryos because the drug inhibits the growth of new blood vessels. Studies were performed on rabbits, which, unlike rats, could absorb the drug at high doses. Further research in the 1990s revealed that this side effect could be harnessed for good, to impede the growth of bone marrow cancers. Such cancers, called multiple myeloma, mostly affect patients older than 60 years of age. Given this age bracket, the FDA assessed that the risk of birth defects could be controlled and mitigated for multiple myeloma patients and approved such use of thalidomide in 2006. Thalidomide’s comeback encouraged drug companies to embark on a new set of trial-and-error cycles, with similar chemicals. Some of those compounds have now been approved for the treatment of multiple myeloma and immune-related disorders like psoriasis and arthritis. Together, these derivatives have enhanced the duration and quality of life of millions of patients across the world.

Despite the complexity of drug regulation, barring anecdotal case studies or the occasional honest error, the FDA has a remarkable track record. When the FDA does encounter unexpected outcomes from its recommendations, the agency incorporates new knowledge into its guidelines through an iterative process. For instance, they issued flawed guidance for years, suggesting new parents avoid exposing infants to peanuts to prevent the onset of allergies when in fact exactly the opposite should have been recommended. Although such errors have been amended in hindsight, the FDA could prevent real interim harm by implementing several improvements to make its decision-making process more transparent and flexible. Yet, its decisions continue to set the benchmarks followed by most other countries, especially when it comes to substances that are either newly developed or not well-understood.

Hence, when RFK Jr. looks at the FDA’s recommendations and alleges corruption, he is making the very mistake the agency aims to avoid: selectively cherry-picking outliers and anecdotes, without weighing the entirety of evidence in the balance. His allegations may come from his beliefs about how the world should be. Instead, it is the FDA's job to only allow claims from their analysis of how the world actually is. And that job is hard. However, the FDA performs this critical and complex role with historically impressive accuracy.

Our new HHS Secretary must improve his understanding of the FDA. Only then can we hope that the resulting improvements he and his team seek would be made in good faith. Otherwise, we run the risk of trading the most effective ingredients that make the FDA a guardian of public health with a flood of untested and potentially toxic substances. And we may not realize the impact of those until it is too late.

Thanks to and for very thoughtful feedback on the drafts of this essay.

Footnote

RFK Jr has also claimed the FDA can’t be truly independent of the drug industry because it relies on user fees paid by pharma companies for its operations. And circumstantial evidence of influence because some former FDA leaders have taken up advisory positions at pharma companies. In this piece, I am focusing on the FDA’s drug regulation activities, but there are benign explanations for these claims, too. For instance, several analyses have found that the user fees benefit rather than interfere with the FDA’s mandate by providing a more reliable source of funding than Congress. And because user fees are pooled, direct influence is constrained. When former FDA leaders advise pharma companies, it improves the efficiency of drug development. Since those advisers no longer work at the FDA, concerns for any quid pro quo in the future don’t hold up.

Keep Reading:

I’m genuinely floored by this piece. It’s not just well-researched - it’s elegantly reasoned, historically grounded, and quietly powerful in how it pulls you from anecdote to insight. You’ve taken something as complex (and often polarizing) as drug regulation and made it human, urgent, and impossible to look away from. I've never given this topic much thought, but the clarity, depth, and care in every line of your writing has made me sit up, gasp, wonder, and as with most things these, hope that reason prevails.

Thanks for a wonderful read shedding light on an important topic. Very well-crafted essay that is appealing to the biotech professionals as well as readable for a layman!